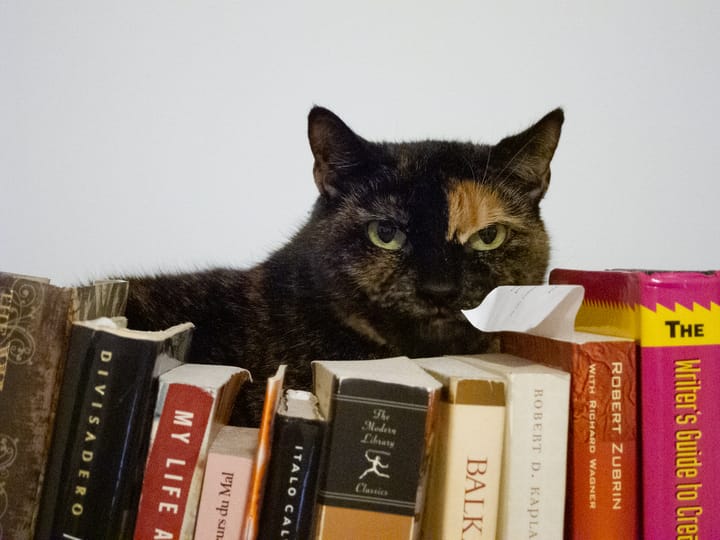

Flinch

New York, NY, USA

M.’s policy, when acquiring new cats, has always been to choose animals that are hard to home. That usually means mature cats, and sometimes ones with a reputation for being difficult or hostile. Nevertheless, even by her standards, Flinch looked like a challenging case.

Born in a feral cat colony in Brooklyn, Flinch was probably about six years old when we got her. She’d probably had at least one litter of kittens before she was trapped and neutered and forcibly introduced to human society. She was, in most respects, not very far from being a wild animal.

During her first few years with us, she was so skittish and reclusive that we named her The Wraith. A friend who looked after her while we were away felt that this was not a good name, and christened her Turtle. Sometimes she was known as The Nocturtle, as she was more active by night. Over time, she became less ghost-like, but she still shied away from any attempt to touch her, so we finally settled on calling her Flinch. We were happy to have her around, but it was pretty clear that she was never going to be exactly cuddly. Or so we thought.

A few years ago, we moved into a new, larger apartment. We also acquired a second cat, so that for the first time she had feline companionship. The effect was magical. She became less afraid of people (one visitor referred to her as “the smaller, bolder one”, which made us laugh). Having been almost mute for six years, she found her voice and learned to use it. She had a habit of appearing silently next to my desk a few minutes before her usual suppertime and making me jump out of my chair with a sudden, peremptory and extremely loud “meow”.

In the early days, when making noise was still a novelty to her, she used to use her voice to still more unusual effect. Her new companion had a tendency to get himself shut in the hall closet from time to time. When that happened, Flinch would position herself in the corridor, more or less exactly at the halfway point between the closet and my desk, and make a peculiar distinctive cry until I came to see what was the matter. Cats do not, officially, have a Theory of Mind. A cat is not supposed to be able to reason about how to accomplish a goal – get another cat out of the closet – using the closest ape as an instrument, much less reason about what the ape does and doesn’t know, and take action to change the ape’s state of knowledge. But it certainly looked as if that’s what was going on. Not bad for a six-pound animal with a brain the size of a smallish walnut.

In perhaps the last year and a half of her life, she underwent another transformation. “She’s become a pet,” M. observed disbelievingly. She allowed herself to be petted. She learned to purr. She delivered affectionate – and sometimes stunning – headbutts. She would join us on the bed every night at bedtime, curling up at the foot of the bed while we read before going to sleep.

We had her for fourteen years. The animal rescuers who trapped her in Brooklyn guessed her to be around six years old, which means that she lived to be about twenty, which is a long life for a cat. Toward the end of her life, she was skinny and a little stiff, probably a bit deaf and possibly partly blind in one eye, but still active and alert, and still learning new things. When the end came, it came very quickly, in the form of a sudden stroke that left her paralysed but not, I hope, in any pain.

She was a funny, quirky little beast, and we miss her terribly already.