Hammer to fall

New York, NY, USA

Strange days indeed. There is a feeling of unreality in the air, a sense that something is happening but nobody is quite sure what.

I find myself thinking in similes. It’s like being in a city under siege. Everyone knows that the enemy is already inside the walls, but most of us can’t quite see them yet. It’s like the Phoney War of 1939, when those who were paying attention could see the outlines of the global conflict to come, but it was still possible to believe that nothing was happening. The image that comes to my mind most often is that of a tsunami: not the gigantic breaking wave of fiction, but the real thing we’ve seen in videos from Japan, a tidal surge that rises smoothly and steadily but oh-so-quickly, swelling faster and faster until it sweeps everything away before it.

Doctors and nurses and health experts aside, we don’t have a real sense yet of how bad this will be. The numbers are all over the place. Optimists think it will all blow over, a flash in the pan no worse than a bad flu season. Pessimists foresee something rather more apocalyptic. Those who have the expertise needed to actually put numbers to it are hamstrung by the same lack of information. We don’t know how the disease works, how it spreads and kills and how it might be stopped. How can we predict what it might do?

We do know that the United States is badly prepared to face a pandemic of this kind. The administration has already squandered precious weeks, dithering and downplaying the threat until it could no longer be ignored, then hastily reversing themselves and trying to pretend that they’d never said any such thing, that they’d been on the case all the time. Even now, the flow of misinformation and obstruction continues, coming from the very top. All of this is going to cost lives. But even without such egregious mismanagement, the US is uniquely disadvantaged relative to most other developed nations. US healthcare, with its inflated costs and malignly-Byzantine insurance system is built to discourage people from going to the doctor until their symptoms become too severe to ignore. The US excels at private health – for those who can afford it – but lags when it comes to public health. That will kill people too.

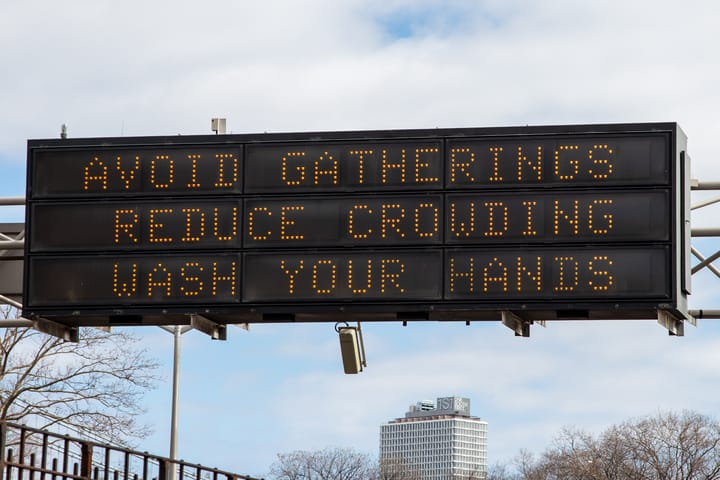

New York – densely-populated, and a global city par excellence – is already a hotspot for infections. Hospitals are describing a ‘deluge’ of cases. In response, the governor has issued a set of instructions aimed at slowing the spread of the infection – non-essential businesses are closed, gatherings of any size forbidden, and individuals urged to remain at home as much as possible. The order goes into effect tonight.

Even before the order takes effect, it’s possible to see the impact of the virus. The streets are not exactly deserted, but they’re noticeably emptier than usual. Many people are masked, although not always effectively: a lot of people seem to treat masks as a kind of talisman and are happy to walk around with their mask covering only their mouth or even dangling loosely around their necks. The greatest density of masks can be found in Chinatown: people in East and South-East Asia have long understood that the point of a mask during an epidemic isn’t for self-protection but to protect others, and they largely know how to make best use of them. Whites, without any similar cultural reference points, seem to be the sloppiest mask wearers.

Many businesses are closed. Those that remain open often post signs to remind customers to keep their distance from each other. The signs may not be necessary: walking around, everyone gives everyone else a wide berth. It’s self-protection, but it’s also courtesy. New York politeness consists of respecting other people’s time and, circumstances permitting, their personal space. Our personal space may now be measured at six feet rather than six inches, but New Yorkers have adapted smoothly enough.

I went for a run yesterday – the gyms are closed, but the governor’s order permits leaving the house for solitary exercise – and found East River Park crowded with people, most doing their best not to come too close to each other. As we spend more and more time locked away in our tiny apartments, the city’s open spaces are the one safety valve we have left.

By 14th Street, a police car was parked on the esplanade, red lights flashing balefully. Two cops leaned on the hood, watching the people walking and running. I don’t know what orders they had – perhaps they were there to break up large groups, perhaps simply to act as a reminder – but for the moment, they seemed happy just to observe and not to intervene.

The city seems to be holding its breath, waiting to see how this will play out. The impression I have is not of fear but foreboding – but with social distancing in effect, it’s hard to gather any very reliable impression of how people are feeling, so I may be simply projecting. We feel only the first hints of whatever’s on the way, the disorientation that comes from the loss of the familiar, disconcerting but not yet terrifying. This is a twilight time. We know something is coming, but no one knows exactly what it will be.

We’re still waiting for the hammer to fall.